What Is Love?

The love stories I have lived and how to redefine love to make it all so much easier.

Last week, I went to an amazing concert with my youngest son. Shane Smith and the Saints played at the Royal Oak Music Theater, and I’d discovered the band while watching the TV series “Yellowstone.” Shaya didn’t know the music at all, but we go to concerts together, so he said yes, and besides I was buying the tickets.

It was a cold night, and we waited outside in line for more than a half hour, huddling into our coats. Then, we got inside the old theater and the standing-room-only front sections were pretty empty for a long time. Shaya got us a great spot at a railing on the second tier, so we were elevated above the floor and could look directly at the band.

And then the music started. It was energizing, loud but not too loud, and uplifting. The band leader told stories about their journey. When you see a successful band on a stage, you think they’ve always been that way, but it’s never that easy. Success is multifaceted, complicated, takes time. The band formed in 2011, and Shane talked about driving around with a burned CD of his first song, “Coast,” begging radio stations to play it. Later, he talked about the 2019 bus fire where they lost everything and almost quit playing music altogether.

The Royal Oak Music Theater isn’t a huge venue. They were the headliner, but in a small space, and I loved that. I felt like I was having a sort of intimate connection with a band not a ton of people know, and dancing, singing, smiling for a few hours in a room with strangers I had something in common with for a short time.

I was in good company. Not only with the fans, but with the band. They’ve worked hard, sweated and strained, and slowly—slowly—rose to some measure of fame. It was hard. They had setbacks. They almost quit, but not quite. Something kept them going, and in time it paid off. Sort of a quintessential American story.

I posted on Instagram and tagged the band. Hours later, they responded to my post. A very human connection, a demonstration that without fans, the band would not have reached this pinnacle. An exchange with mutual benefit.

I had a transformation that night. Looking around at the cowboy boots and hats, I felt a kinship with an element of American society that too many scorn. A down-home, hardy, frontier element of this country that I was suddenly proud of. Our ability to innovate, to face challenges, to explore the boundaries, to build. I’m reading a lot into a concert, I know, and it’s a pretty privileged place to be, but cut me some slack. We’re living in hard times, and I found a measure of joy and hope in the music.

It’s why I write, I think. To connect with strangers. To offer hope. Relatability. Humanness with all our flaws and frailties, and redemption at the end of it all.

My son is leaving in a few days, and I’ll miss him greatly. He’s going west, and the American west is so hyped up on metaphor and meaning. My son is going there, literally and figuratively, out on his own for the longest stretch of time away from home, and he’s scared, he’s told me, but excited, and going anyway, surmounting the challenge and the fear, to see what’s around the bend, over the horizon.

How Do You Define Love?

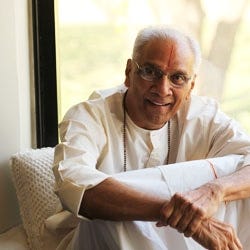

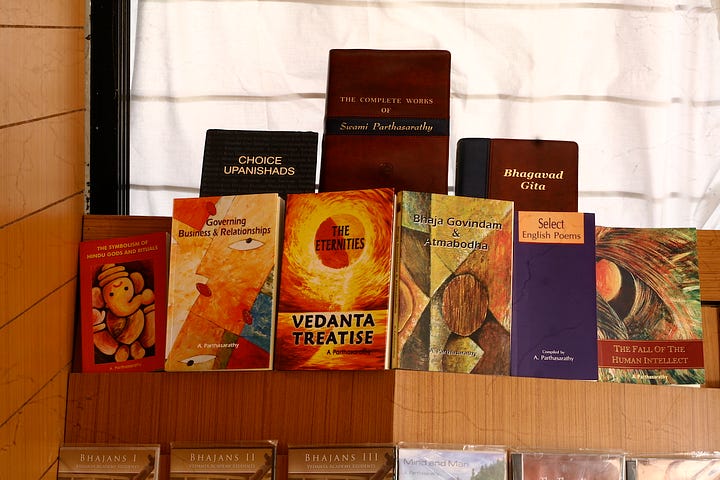

Between my first and second marriages, I met a Swami. He was soft-spoken and calm, and he came from India to sit on the floor of high-ceilinged living rooms and teach eager Americans like me how to live a good life.

There were recommendations for what to eat (no animals), when to wake each morning (4 a.m.), and how to have perspective about what matters.

Love, he said, isn’t preferential attachment. It’s universal understanding. You can love the woman at the dry cleaner counter. You can love the server in a restaurant. You can love that guy in high school who spread a rumor about you. Or at least try to.

This new way of defining love broke my world wide open. No longer did I live in the realm of ‘80s movies where girl-pines-for-boy-and-eventually-lands-him-after-playing-a-lot-of-cat-and-mouse-games. This kind of love required each person to stand tall and strong in their own emotional frame, in their body, solitary, aware, awake, and only then—ONLY THEN!—look for someone of equal stature to share space and time and life with.

It’s the best kind of love, really.

We’re just past Valentine’s Day, and my husband and I never do anything for it. Feels forced. Artificial. We love each other every single day. I wake earlier than he does, and each morning, he comes downstairs quietly and finds me, gives me a soft sweet kiss and smiles good morning.

He does the dishes. I cook. Sometimes he cooks, and I do the dishes. He does the grocery-shopping, though I make the lists. He does the laundry. I neaten the couch cushions, fold the blankets, scrub the kitchen sink. We both work to earn money for our life together, and I like nothing more than to have a weekend with no plans where we can sit on the couch or wander in the woods or go to a cafe and read our separate books and sip our coffees and smile at each other.

It’s a nice kind of love. We miss each other when we’re apart; we are both eager to travel solo as well as together. It’s symbiotic. Understanding. Two whole people choosing to come together.

In my recent book, FOREST WALK ON A FRIDAY: Essays on love, home and finding my voice at midlife, there are a lot of love stories. Young love, movie-love, arguing-and-making-up love. There are stories of the lovers I wished would marry me but who didn’t and I’m glad about it in the end. There are stories of my first marriage, its demise, and my rebirth as an independent, confident thirty-seven-year-old. And stories about finding Dan, the love of my life and a second chance at marriage.

My favorite essay, though, is the first one, “The Roads We Travel.” It’s about a relationship I had in my 20s with a much-older man who had been my editor when I worked in New York. He lived on the East Coast and I was in Michigan, and we drove a lot to see each other and then we drove across the country for two weeks together and it was a movie kind of love.

I wish had photos from that time. I’ve searched, and I can’t find any. We had no phones, or not the kind with great photography like today, and I may have lugged my old Canon with its film wound inside the dark innards of the camera, but I can’t find any of the prints. It’s a shame, because I remember vivid color: the Corn Palace, Wall Drug, long stretches of open Midwestern road, the parched earth of Wyoming, the view from his father’s house with a cup of hot coffee as the sun rose, the sound of a spilling river fast in its path outside a friend’s house in the north of Wyoming.

I remember the hike we took in the Bighorn Mountains and the cold of the lake we stopped at for a picnic lunch. My memory is an art museum with curated galleries, and I can only walk through it, never stopping to gaze at the image and its hidden meanings.

In the essay, I braided that relationship with my exploration into a more observant kind of Judaism. Just as I’m getting to know Chris and falling for him and wondering if we are meant-to-be, I am loving the idea of observing the Sabbath, not driving or working for 25 hours from sundown Friday until three stars shine in the Saturday night sky. Of course, these two desires are not compatible, and so one has to win out over the other in the end.

But when we’re young, we don’t think we have to make choices. We try to find ways to have everything all at once. My kids are those ages now, and they talk about their desires, their relationships, how they can have it all. I hesitate to tell them that they might not be able to in the end. It’s not my place to say it. They have to learn for themselves, and I can guide them with cautious words to think about things, but ultimately it’s on them, isn’t it?

That may be the hardest part of parenting, letting them make the mistakes I can see coming. I’m not sure I would listen, even now, if someone told me I was going down the wrong path. I’d deflect—who are they to tell me what to do!—and I guess in the end, we’re all so sure we know better, right?

My youngest will soon be out on trail in the Rockies, having experiences and growing up and learning how to be independent. He’ll learn how to be safe in an avalanche and he’ll climb the craggy rock face of an old mountain and he’ll paddle down cold waters as spring comes on with flowers and grasses and warmer air and the sound of birds. I’ll miss him greatly, and I look forward to meeting the person who comes home in the end.

Write With Me in San Miguel!

My January 2026 writers retreat in San Miguel de Allende, Mexico is open for application and it’s already half-full! I’ll be hosting this retreat with my friend and fellow writer, Christopher Locke, who is amazingly talented at teaching and writing. We’ll be writing, hearing from bestselling authors, hiking, visiting the hot springs, participating in an authentic Mexican cooking class and more! We’re taking over a gorgeous little inn, Casa de la Noche, and there are limited spots, so if you’re interested apply now! We are already nearly half full! All details can be found here.

Thanks for reading Lynne Golodner’s Substack. This newsletter publishes twice-monthly and focuses on topics relating to identity, belonging and finding community along with Lynne’s writing and publishing journey. It would mean so much if you’d care to become a paid subscriber. It’s hard work to write for a living, and if you find value from these words, please join the ranks of those who support it. All love, Lynne

Lynne, I wrote about love too this week in my Substack. What is Love? What a theme. Always enjoy your newsletter. Your son will love the west. I live in northern Wyoming, where the people and the place are oh so special….All the best to you in love and life.

Wonderful essay, Lynne!